Lorne Greene is a national treasure. We literally learn about

him in school here in Canada; it’s not optional. He’s up there with Walter

Pidgeon, Christopher Plummer, and Leslie Nielson, all of whom we also learn

about in school during a unit called “Northern Lights” – we watch documentaries

about their lives narrated by Lorne Greene. (Yes, Lorne Greene narrates his

own. Yes, it’s in third person.)

Anyway, LG’s b-day was on February 12, but I was doing Mardi

Gras and I’d already stopped in the middle of that for Inventors’ Day and Valentine’s. And yes, we do need a Lorne Green day even though we’re

recapping Bonanza in chronological

order, because Lorne Greene is important.

And all that is why we’re watching an episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents that features TV’s best loved dad in a

very different kind of role.

This time around, Hitch is perusing the want ads in search

of a cushier gig than the one he’s got. He finds one that’s looking for a

charming, handsome, witty TV host – contact Alfred

Hitchcock Presents if interested. (Confession time: I never think these

segments are funny. I don’t know if that’s just me.)

Our story for today is called “Help Wanted” and it begins

with the Crabtrees, a middle aged couple with a big problem. Mr. Crabtree has

lost his job at the age of fifty-two, and Mrs. Crabtree is ill. The nature of

her illness isn’t specified, but they’re having a tough time affording her

treatments and she needs a very expensive surgery. They’re sitting in their

tiny apartment, Mrs. Crabtree convalescing on the sofa with her knitting while

Mr. Crabtree polishes off a letter he’s writing at the kitchen table.

Mr. Crabtree, by the way, is being played by Canadian actor

John Qualen. I point this out because of nationalism. Also, Qualen was

incredibly prolific and probably somebody who you’d know by voice or face, if

not by name.

Mrs. Crabtree is Madge Kennedy, an actress best remembered

for being Aunt Martha on Leave it to

Beaver. This is her first of five appearances on Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and she would also feature in an episode

of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (a kind

of revamp of the same format extended to one hour under the new title).

For the last few months, Mr. Crabtree has been sending his resume

to employers he finds advertising in the Help Wanted section of the paper. It

hasn’t been going well. For starters, he’s fifty-two and it’s hard to find a

new job at that age. And then there’s the little detail of… the incident.

It really wasn’t Mr. Crabtree’s fault. He’s such a quiet,

gentle sort of person, and the timing of the whole thing couldn’t have been

worse what with Mrs. Crabtree having all of those medical expenses. He worked

for the firm of Stowe and Baker for thirty-one years, and then they unceremoniously

kicked him to the curb so that they wouldn’t have to pay him retirement

benefits. Benefits he needed to

support his wife.

In the heat of the moment, he says he was on fire with shame

and rage.

“In fifty-two years it was the only time I really lost my

head,” he tells Mrs. Crabtree apologetically. “It really makes you wonder how

far you might let yourself go.”

Mrs. Crabtree soothes him and says that it’s all over with,

and there’s no use getting worked up about it again. It’s kind of sweet,

because Mr. Crabtree’s version of “worked up” is shouting and pacing.

They’re an enormously likeable couple trying to make their

way in a backwards, ageist world. I have nothing but contempt for the personnel

manager at Stowe and Baker.

Mr. Crabtree hopes that this is the letter that’ll land him

a fresh start and tucks it in an envelope.

A week or so later, the phone in the hallway rings.

Back then, it wasn’t uncommon for an entire floor of a small

apartment building to have a shared phone and a shared bathroom. The “apartment”

would be a bedroom, kitchenette, and living space.

Bursting with a mixture of desperation and hopefulness, Mr.

Crabtree jumps out of his front door and answers. It’s for him! And it’s about

his letter of application!

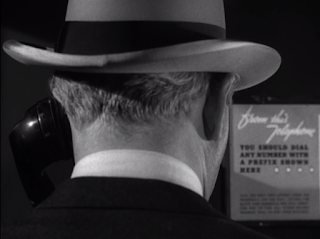

We see the back of a head, neatly clipped hair peeking out

from under an expensive and stylish hat, and we hear a voice. A familiar,

baritone voice.

Well, familiar to the audience. Mr. Crabtree has no idea who

this is yet, except that he seems very impressed with Mr. Crabtree’s potential.

Everything is in order, and there’s just one thing that this mysterious

gentleman would like to discuss. Naturally, since the only firm Mr. Crabtree

had ever worked for was Stowe and Baker, they were the only option to be called

for a reference. The personnel manager was reluctant to discuss the matter, but

he did reveal that upon being terminated, Mr. Crabtree attacked him. Physically.

“Yes, I’m afraid that I did,” Mr. Crabtree says because he’s

not dishonest, he just flipped out on a personnel manager one time, it happens.

“I don’t know what came over me. The injustice of it, I guess. You see, I

desperately needed that job. My wife’s been ill. It could never happen again, I

promise you.”

Lorne Greene says that’s all very good and exactly what he wanted to hear.

Mr. Crabtree can expect a visit from a representative of our

mysterious nameless man. A secretary will call on him within the hour to

arrange the particulars of the job.

Looks like things are looking up for Mr. Crabtree thanks to

everyone’s dad, Lorne Greene! Yay!

But the hour goes by with nobody coming to the door.

Mr. Crabtree paces his living room in his good suit,

fretting over the delay. Every sound he hears on the landing pricks his ears,

and he opens the door to see if it’s her. Mrs. Crabtree is lying on the sofa

with her pillow and blanket, and she observes that it’s kind of weird the way

all of this is going down. But before Mr. Crabtree has a chance to think about

that, the knock finally sounds.

The secretary turns out to be a very efficient looking

blonde in glasses that weren’t actually in fashion then but are now. She

introduces herself as Miss Brown, and takes a seat across from Mr. Crabtree at

the kitchen table.

She gets right to the business of explaining the job. It

turns out that Mr. Crabtree is going to be some kind of media consultant. That

sounds neat! What he has to do is send in confidential reports about magazine

mentions. Every day, he’ll get a whole bunch of magazines with certain words

and products he has to look for; his job is to note how many times in each

publication the words and products are mentioned. So he’s got a list that says,

like, toothpaste and also Colgate toothpaste. He’ll go through a magazine and

note that it mentioned toothpaste four times, and Colgate toothpaste twice. So

those other two times were opportunities the people at Colgate missed.

Miss Brown goes on to say that Mr. Crabtree will be

working alone, in his own office, with no assistants. His reports will be

mailed to the same box he mailed his job application to.

This part kind of overwhelms Mr. Crabtree. Mind-numbing word

scans are something he can handle, but this sounds to him like he’ll be a

supervisor or department head, and he’s used to being a clerk. This sounds like

a lot of responsibility, does that mysterious man on the phone know that Crabtree has never been in management?

(Psst, Mr. Crabtree. You’re the only person in the office.

The pressure isn’t as intense as you think it is.)

Miss Brown is like: “Yeah, we’re pretty sure you can handle

this.” She gives Mr. Crabtree the address of his swanky new office full of no

one, and the key to it, and asks if he can start tomorrow. Nine to five, half

day on Saturdays. At first, Mr. Crabtree is all: “Tomorrow? I think I’ll have

to check my schedule…” Because he really doesn’t feel comfortable being thrust

into leadership. Of himself.

But then Mrs. Crabtree, who is still sitting in the living

room and is behind Miss Brown, signals to her husband to go for it. She

believes in him. Work is work. You can do this, Mr. Crabtree.

He accepts the job.

Awesome! His salary will be one hundred dollars a week, if

that’s satisfactory. (That’s around nine hundred dollars in modern U.S.

dollars. For perspective for non-American readers, the current average weekly

wage is seven hundred and fifty dollars.)

Mr. Crabtree tries to play it cool, but ends up stammering

that it’s a very generous amount.

He’s going to get his salary in cash every Saturday by mail.

I don’t think there’s anything weird about that. I mean,

mysterious Lorne Greene – he needs a name, let’s call him Bart Nightcrew –

probably has lots of non-illegal reasons for paying somebody’s salary in cash.

It seems perfectly normal.

Miss Brown then informs Mr. Crabtree that his work is both

crucial and highly confidential. Do not tell anyone about your marketing

research, it’s totally on the level but also a secret. No more questions. Ever.

One hundred dollars a week is enough to smooth over the

wrinkles and ease the doubts. With that money, Mrs. Crabtree can get her

treatments, and once they’ve saved enough, she’ll have the operation. Mr.

Crabtree thanks Miss Brown and shows her out. When the door closes behind her,

Mr. Crabtree beams with joy. The metaphorical ship has finally come in.

As it turns out, the office Mr. Crabtree is to work from is

located on the twenty-second floor of a skyscraper. He’s got his own little

sign on the door that reads: Crabtree Affiliated Reports.

Inside, the space is quite small, but it’s big enough for a

large desk and chair, a filing cabinet with a fern on top, and a hat rack. Swanky!

Our beloved Mr. Crabtree couldn’t be happier. Especially

about the view! He can see all of the city from his giant windows. They open

outward, though, not up. And there’s a strangeness to the proportion of them

compared to the rest of the room. They seem… too low. But that’s probably my

imagination.

Just to test everything out, Mr. Crabtree opens up those foreboding

death gates and breathes in the crisp city air. He can hear the traffic noisily

going about its business below, and decides that it’s too distracting, so he

closes them back up and parks at the desk.

He finds a small key that works the desk drawers, and inside

his magazines are waiting for him. Excellent. Now he can get started right away

on his report. And as he does, he sees

stationary with his name and title and department on it. He smiles with the

deep satisfaction of a man with small goals.

So, a few weeks go by. One morning, Mr. Crabtree is getting

ready to go into the office while Mrs. Crabtree enjoys a cup of coffee. She’s

got a little more pep than the last time we saw her, which is nice because

these are nice people.

It’s actually kind of noteworthy that the dread in the

episode isn’t coming from anything other than the Crabtrees being so likeable

and the details of the job being ever-so-slightly off. The tension builds as

you wait for that off-ness and Crabtree to collide.

And collide it will, this very morning at the offices of

Crabtree Affiliated Reports…

After a brief conversation where we learn it’ll only take

two more months of saving from this job and Mrs. Crabtree can go into the

hospital, Mr. Crabtree heads in to work.

He’s surprised to find someone sitting in his chair.

“I seem to have startled you,” Mr. Nightcrew says, in a very

blasé manner.

At first, poor Mr. Crabtree doesn’t connect the dots that he’s

talking to the man who employs him. He’s not rude or anything, just baffled.

(Honestly, Mr. Crabtree. How could you forget a voice like that?)

You should probably know that the bulk of the episode is

comprised of these two talking for the next ten minutes. But, it works. It’s an

episode with three locations, five major roles, and tons of dialogue, but it’s

a really strong dark script, and it gets there without anybody sawing their own

foot off.

Nightcrew introduces himself as Mr. Crabtree’s employer, and

Mr. Crabtree is the picture of cordiality as he says what a pleasant surprise

this is, and asks for the gentleman’s name. Of course, Nightcrew doesn’t give

him a name, because as far as the story is concerned he has no name, which is

why I had to make one up for him in order to describe his actions.

Mr. Crabtree goes on to say how enjoyable he’s been finding

his work, and how he hopes his reports have been satisfactory. Nightcrew barely

listens as he opens those great big windows, and takes a satisfied glance at

the long drop to the pavement below.

He tells Mr. Crabtree that he’s been burning his reports.

As in lighting them on fire as soon as they come in the

mail.

“You must be joking!” Mr. Crabtree insists.

“If you knew me better, you’d realize that I am almost

totally devoid of a sense of humour. That is one of the penalties of devoting

the entirety of one’s energies to accumulating a vast fortune.”

He says almost,

though. So the question is what does make him laugh? Little dogs in lifejackets

paddling around in backyard pools? Misprinted signs? Faustian irony?

Mr. Crabtree asks the other question on everyone’s mind: why

pay him to write reports destined only for the fireplace? What’s this all

about?

Nightcrew assures him that this is about nothing more than

needing a loyal, conscientious employee who can be trusted with an important

and difficult assignment. And if he completes this assignment, he’ll be

rewarded with one year’s salary in advance and no more reports to file.

That sounds a little too amazing, doesn’t it?

Of course it does.

Oh, poor desperate Mr. Crabtree. Poor, deeply in love Mr.

Crabtree, with his ill wife. How he needs this money. How it’s the one thing

that can cause him to do outrageous things. Things he never, ever would

ordinarily do. Like hurt people.

Maybe even murder them.

And that, of course, is the difficult assignment.

Naturally, Mr. Crabtree starts off by saying no. He’s not a

murderer, and flying off the handle at that one dude that one time doesn’t make him a murderer! But it turns out

that the incident was much worse than we’d been led to believe, and that the

personnel manager had almost been killed by Mr. Crabtree, who was restrained in

the nick of time.

Still, Mr. Crabtree insists, that doesn’t mean he’s willing

to kill someone in cold blood.

“I envy you, Mr. Crabtree. You have emotion, while I am

entirely devoid of feeling.” Nightcrew says wearily. (I’m not going to tell him

envy is an emotional response because he’s doing a murder speech right now and

it wouldn’t be polite.)

Okay, so why doesn’t Mr. Roboto over here kill this victim

himself if he has no pesky feelings of doubt or guilt like poor old Crabtree

does?

Well, it’s more to do with the who and why of the victim

than anything else. You see, years ago – before he lost the use of his emotions

in that terrible skiing accident – Bart Nightcrew fell in love with a woman who

had been recently widowed. Or, at least, everybody including the woman herself

believed her first husband to be dead, even though he was never legally

declared dead. He was very much alive, as you’ve no doubt guessed.

(It’s like if Move

Over, Darling had been about Polly Bergen trying to have Doris Day killed

on the sly.)

And for the past five years, Nightcrew has bought husband

number one’s silence for “a monthly sum that would stagger you imagination.”

Our imaginations are pretty hard to stagger, and this was made in 1956, so he’s

probably wrong about that. It’s probably like seven thousand dollars.

Mr. Crabtree points out that blackmail is illegal and

Nightcrew could report this jerk to the police. But no, the scandal wouldn’t be

worth all that, and there’d be no guarantee that Mrs. Nightcrew wouldn’t be

charged with bigamy. Nope, definitely have to solve this with murder, there’s

no obvious non-murder options that Nightcrew hasn’t already considered.

“But you have no guarantee that I won’t blackmail you…” Mr. Crabtree notes, in a totally unthreatening

way. It’s more like he can’t believe this is somebody’s actual plan. I like

this guy, he asks the real questions.

He then suggests that he go to the police right now, and see

what they make of Mr. Nightcrew and

his assignment.

As it happens, Nightcrew has thought of all of this and

more. His plan is perfect, just like all the plans on Columbo. Most

importantly, Mr. Crabtree doesn’t know his name, where he comes from, or how to

verify his existence. He took out the ad in the paper anonymously, and while

the post office might be able to connect the box to him, so what? Even if they

verify that Crabtree sent a letter of application, Nightcrew has his copy of a

response he sent explaining that the position was filled. The office was rented

in Crabtree’s name, the magazine subscriptions were bought in Crabtree’s name,

everything was paid for in cash, and the reports have been burned.

And Miss Brown? She was never really Nightcrew’s secretary.

It would be impossible to prove she even existed.

“The reports!” Mr. Crabtree remembers, pulling the latest

one from his desk drawer.

“Ah, the reports. A meaningless jumble of words and numbers

that you persisted on sending me, despite my letter that I had no use for this

service.”

Nightcrew has arranged everything that should Mr. Crabtree

go to the police, they’d probably end up locking him away in an asylum instead

of doing anything to Nightcrew.

Mr. Crabtree asserts that an asylum might be preferable to

being hanged for murder.

But nobody’s going to be hanged, Mr. Crabtree! Because the

murder itself has been as meticulously organized as the positioning of the

murderer!

It’s going to work like this:

The blackmailer is going to come by the office in the

morning and ask for “a charitable contribution.” Mr. Crabtree will then give

him the envelope that Nightcrew is supplying him with right now.

The office, you’ll remember, is small, and the desk is a

little over-sized. This was all carefully arranged so that the only comfortable

place to stand is by the great big windows. It is while the blackmailer is

standing by these windows that Mr. Crabtree will give him a shove. It doesn’t

have to be anything dramatic, just enough to plummet him to his doom.

Of interest is the fact that this blackmailer never looks in

his envelope when he picks it up. He’s extremely ritualistic about his money.

But there’s no money in this month’s envelope. There’s a carefully forged

suicide note. The police won’t think a thing about it. And with Mr. Crabtree

being on the top floor, any onlookers will suppose that the blackmailer jumped

from the roof.

It’s all been thought out to the last detail.

Now Mr. Crabtree has to make a choice. He can kill this

blackmailer, get a great deal of money, and go about his life. Or, he can

choose not to kill the blackmailer, and never see or hear from Nightcrew again,

and his salary will automatically cease. Back to square one.

“For your wife’s sake, Mr. Crabtree, I think you’ll have to

do it.”

Nightcrew leaves, and the deciding begins.

Mr. Crabtree stays up all night, sitting in his armchair,

twisting the envelope lightly between his hands. He’s not good at making tough

choices, this is the whole reason he didn’t want to be in management! But then,

he’s proven that he can be a little dangerous when he feels his wife’s health

is on the line…

He’s not a bad man, certainly not a murderer. Is he? Would

he have really killed that personnel manager if he hadn’t been stopped?

Mrs. Crabtree calls to him to come to bed. He needs his rest

or he won’t be any good at the office tomorrow.

He chuckles morbidly, tiredly, at the idea of that. Too

sleepy to push a man out of a window.

“Laura,” he asks Mrs. Crabtree, who turns out to be the only

person in this episode with an actual first name, “how did you feel today?”

“Oh, I’m feeling a little better every day!” She beams, “Dr.

Foley’s coming tomorrow, do you think I ought to ask him when I should go into

the hospital?”

Mr. Crabtree looks at the envelope, closes his eyes tightly,

and nods.

She should ask.

The next morning, with nauseated determination, Mr. Crabtree

crackles into his office like every step is giving him an electric shock. He

fumbles to hang up his hat, doing his best to be decisive and cold, but never

quite making it.

He opens the windows to get ready, and closes them almost

immediately. Looking down that long tunnel of concrete that leads to the

pavement below, it all becomes too much for him. That is a hell of a way to

die. A hell of a way to know you killed someone.

It’s eating him up.

He throws the envelope on top of the desk, and it waits

there. As much of a weapon in his mind as any gun or knife or noose. A venomous

snake instead of a white square of paper. And next to it, a photograph of dear

sweet Mrs. Crabtree.

The tension is so wonderful in this moment, I’m going to

pass out some kudos to the writers. This episode was adapted from a story by

Stanley Ellin, who had a number of works made for television, including one for

Circle of Fear that (if my planning

skills don’t let us down) is on the recap schedule for the near future. The

adaptation was worked on by Mary Orr, who also wrote All About Eve, and her husband Reginald Denham. This was in the

early days of TV, when many Hollywood writers were still trying to figure out

how to best write for the medium, and it looks like these two had a little help

by way of a teleplay credit belonging to Canadian Robert C. Dennis.

It was directed by James Neilson, who would go on to work on

some of our faves, including Bonanza,

Have Gun – Will Travel, Adam-12, The Rifleman, Zorro, Batman, The Donna Reed Show, and Longstreet.

His resume reads like my to-watch list.

I guess you’re wondering what Mr. Crabtree is going to

choose, though.

And, frankly, so is Mr. Crabtree.

He opens the windows in a burst of decisiveness, and then

immediately goes to close them again. But before he can, a knock sounds on his

office door.

His voice quavers as he mumbles for the person to come in.

He has to repeat himself, louder, more firmly.

The man who enters smiles, takes his hat off and asks Mr.

Crabtree if he would like to make a charitable contribution.

Crabtree can’t even look at the guy. He snaps that it’s all

ready, all in the envelope.

He’s about to let the guy leave, when it all washes over

him. He starts raving about how his wife will be an invalid for as long as she

lives because of the parasites like this blackmailer. He says he wishes he had

the nerve to kill him, and stands up abruptly.

It’s an accident when the man falls.

There’s so little room to move around in the office, and the

man is so startled by Mr. Carbtree’s outburst, that he takes a step back.

Mr. Crabtree reaches for him, but it doesn’t do any good. It’s

too late.

People on the street below scream. Across the way, far

enough to slip away without being conspicuous, Nightcrew watches as the crowd

begins to gather and murmurings of a jumper ripple through the onlookers. He

seems frightened and thrilled that it’s been done.

Quickly, he tucks the envelope with Mr. Crabtree’s payment

into the post box, then ducks in to a nearby payphone. He dials, as cops race

by to begin clearing the scene and investigating the jump.

Back up in the office, Mr. Crabtree is devastated. His large,

mournful eyes are on the brink of tears, and his mouth is a shaky frown.

The phone in front of him rings.

He answers, and tries to explain to Nightcrew that it was

all an accident.

“Your rationalizations don’t concern me, Crabtree. All that

matters is you’ve completed your assignment. Your year’s salary is in the mail.

You’ll never hear from me again.”

Mr. Crabtree hangs up.

A few hours later, the police are making their rounds

through the building. A detective named Grant asks about whether or not the

window was closed, if Mr. Crabtree heard anything or not, if anyone unexpected

had been by the office. The small lies come easily to Crabtree, and the police

are satisfied he had nothing to do with it. They’re about to leave when he

calls after them:

“Was it a suicide?”

“All the way. We found a note in his pocket.”

Somewhat relieved, Mr. Crabtree goes back to the business of

closing out the office. He’s wrapping up a parcel when somebody lets themselves

in without so much as a knock.

He’s a short man, in a draped suit and tilted fedora. His

eyes are expectant, his face smiling with the chiseled greed of a fellow who’s

used to getting what he wants.

He tells Crabtree he’s here to pick up a contribution from a

mutual friend. He doesn’t think he has to name any names.

It dawns on Mr. Crabtree what’s happened.

“The wrong man got it. You came too late. Only it wasn’t

money, it was your suicide note.”

The blackmailer is seriously taken aback by this and asks

what that’s supposed to mean. Mr. Crabtree says he’ll have to take it up with

the man he’s blackmailing.

“And if he asks for me, tell him I no longer work here. As

far as he’s concerned, I never existed.”

Mr. Crabtree puts on his hat and leaves.

And that’s the story! It seems like we’re not supposed to

feel too badly about a charity collection man accidentally falling to his

death, but I do. That guy wasn’t doing anything wrong.

As for Lorne Greene, it was enough of a shock when he found

out his blackmailer was alive and he’d spent all of that money for nothing, he

rarely played villains again.

Alfred Hitchcock comes back to close out the show for us,

noting that Mr. Crabtree’s final manoeuver was “sneaky, but brilliant.” He

promises to be back next week with another story.

He might not be, but I’ll be back tomorrow with an episode

of The Twilight Zone! So watch this

space!

No comments:

Post a Comment